“Individuals seek truth. Groups seek consensus.”

This pretty much explains all of society and politics, right here. ☝🏼

A place for thinkers

“Individuals seek truth. Groups seek consensus.”

This pretty much explains all of society and politics, right here. ☝🏼

Today was my grandma’s birthday, on my mom’s side. A lot of people are important in my life, but without question, the two people who had the most influence on me growing up, who most formed me as a person, and who I am most like, are my grandmas. The ashes of my dad’s mom reside on my bookcase, along with a pack of her favorite cigarettes, and a seashell that she found on her lone trip to Florida, one of the few times she had a chance to travel out of state (it could actually be the only time, as far as I know).

My dad’s mom is responsible for my raunchy sense of humor, my ridiculous, outrageous laughter, and my generally mischievous demeanor. My mom’s mom is responsible for my political consciousness, my sense of justice and fairness, my longing for peace between all people, and my overriding desire to see the world become a better place.

Today, on her birthday, I want to share a few words I wrote to celebrate her life when she passed away in 2007. God bless you, Ceil.

I’d just like to say a few words about the tremendous debt that I owe Ceil. Until I came back a couple weeks ago, I hadn’t really realized how much she had taught me, how much of my personality and my interests were due to her influence. Everyone here knows what a sweet, giving person my grandma was, how she gave her time to help individuals, but not everyone may be fully aware of how dedicated she was to politics in years past, how tirelessly committed she was to doing what she could to make the world a better place.

When I was a little kid, Ceil was constantly going to meetings and taking trips for one of the numerous political organizations she belonged to. For my entire life, words like “union” and “League of Women Voters” have reminded me not of politics, but of my childhood and my grandma. One of my first memories is of her taking me up on a podium and introducing me to Walter Mondale, so he could shake my little 5 year old hand. By the time I was in elementary school I could tell you why I thought Democrats were good, Republicans were evil, and why unions were vitally important to workers. I remember how once in fourth grade I shouted an angry, semi-revolutionary statement against Ronald Reagan at my teacher in front of the whole class when I thought she was talking him up.

I have since learned a lot and changed my mind about some of my elementary school political positions, but there is no doubt whatsoever that I have my grandma to thank for teaching me at an early age to think about the world around me, about the people in it, about what’s right and what’s wrong, and for teaching me by unintentional example to always do the right thing, to speak up when I see injustice, to get involved in and be engaged with my society, and most of all, no matter what happens, just to never give up and to never stop trying to do better and to contribute what I can to my society.

Though she was quiet and unassuming, my grandmother was an extraordinary person. As did many people of her generation, Ceil had a hard life, and went through hard times that I can’t even imagine, both because of the times she lived in and because of the curveballs life threw her way. But through it all she never stopped smiling. Ceil, despite all she went through, never developed that hard, bitter shell that most of us get when people and life do us wrong. Through it all she still trusted people, saw the good in everyone, and took her greatest pleasure from seeing that other people were happy. She really did care for everyone and would never say a bad word about anyone. My grandma, despite growing up poor and not having the advantage of a college education, became a political leader in her community, read fine literature (some of it to me when I was little), and sincerely enjoyed her life and the people in it up to the very end. I’m in debt to her for my political consciousness, a large part of my intellectual development, for the example she gave me of how to care about and forgive other people, and most of all, for the unflagging support and love she gave me my entire life. If I could see her again I’d just want to say thank you, I love you, and I miss you terribly.

Here’s a little optimism to start your weekend

When I was a young socialist (yes, you read that right), I had a lot of opinions about what people and society should do with their money. But I didn’t know a single thing about actual economics. No, not one thing. I was completely ignorant even that I should know things about economics, I was deep into the realm of Rumsfeldian “unknown unknowns.” I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and this meant that there was no way for me to learn on my own and teach myself to a better understanding. I was ignorant of my ignorance, which I now know is itself a well-understood and studied phenomenon: part of the condition of being ignorant is that you don’t know you’re ignorant. It’s kind like how part of being crazy is that you don’t know you’re crazy.

There’s even a fancy name for it:

This is a topic worthy of discussion in its own right, but I just want to mention it to paint a picture of where I myself have been regarding the topic of economics. This abstract basically describes my level of economic understanding in my 20s:

People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains. The authors suggest that this overestimation occurs, in part, because people who are unskilled in these domains suffer a dual burden: Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it. Across 4 studies, the authors found that participants scoring in the bottom quartile on tests of humor, grammar, and logic grossly overestimated their test performance and ability. Although their test scores put them in the 12th percentile, they estimated themselves to be in the 62nd. Several analyses linked this miscalibration to deficits in metacognitive skill, or the capacity to distinguish accuracy from error. Paradoxically, improving the skills of participants, and thus increasing their metacognitive competence, helped them recognize the limitations of their abilities.

In essence, we argue that the skills that engender competence in a particular domain are often the very same skills necessary to evaluate competence in that domain—one’s own or anyone else’s. Because of this, incompetent individuals lack what cognitive psychologists variously term metacognition, metamemory, metacomprehension, or self-monitoring skills. These terms refer to the ability to know how well one is performing, when one is likely to be accurate in judgment, and when one is likely to be in error.

For example, consider the ability to write grammatical English. The skills that enable one to construct a grammatical sentence are the same skills necessary to recognize a grammatical sentence, and thus are the same skills necessary to determine if a grammatical mistake has been made. In short, the same knowledge that underlies the ability to produce correct judgment is also the knowledge that underlies the ability to recognize correct judgment. To lack the former is to be deficient in the latter.

If you would like to know more about the Dunning-Kruger Effect, you can read the Wikipedia article here, view and download the full paper here, or read it online in html here.

So there I was, Dunning-Krugered as hell about economics. So what happened? What always happens with me: I started arguing with people. I took my DK’d self with my DK’d ideas, and brought them all cocky and manly like to other nerds and wonks, and got my ass severely kicked and handed to me over, and over, and over again, in debate after debate. I literally cannot count the number of debates I lost, and how many times I didn’t just lose a debate, but basically got woodshedded like a red-headed stepchild.

[This was in my mid-20s, after a five year stint in the army, while an undergraduate at Columbia University]

But two things have saved me in life from having this sort of thing destroy me and ruin my self-confidence: one, that I can take a loss, and two, that I can learn from one. I would walk home from an argument outside of class or outside a bar, swearing and muttering to myself all the way home (on the inside, I hope). Mostly for being so stupid and so wrong, and occasionally, for being so arrogant. And each time, mad as I was, I was even more grateful, for having been so violently and suddenly disabused of such erroneous ideas. As Sam Harris once said: I don’t want to believe a wrong thing for one minute longer than I have to. So I welcome intellectual challenges and people who can teach me something, or better yet, correct any wrong ideas I currently have.

Of course, as time went on, I sought to educate myself. Once I realized this was an intellectual weakness of mine, I read an uncountable number of articles on economics, sought out people who knew more than me (now to ask questions, rather than debate), and read a few foundational econ books. I realized through the course of these conversations that while I considered myself a policy wonk and a politics nerd, I was lacking a fundamental pillar of understanding these issues: that of basic economics. I realized that I was functionally illiterate in one of the core areas necessary to understanding our world, and to having an educated opinion on political topics. It was one of the most humbling intellectual realizations of my life, and maybe the first real moment and topic where I found myself sitting in silence with an awareness of my own profound ignorance of something so obviously important, if you actually knew anything about the world.

The reason I’m writing this essay is that I have come to realize that my own ignorance, while shameful and appalling, is not unique. In fact, I think it is the norm. Now just like I recently stated that I’m no mathematical genius, I’m also no economics genius. I’m not an economist, even by hobby, let alone trade. I’m no expert on economics or economic theories, even a lay expert or hobbyist. But here’s what I’ve come to fear/realize: I simply know basic economics very well, and that means I know more than 95% of people I meet. And I don’t mean 95% of people in the mountains of Arkansas. I mean 95% of college educated people with otherwise sophisticated and nuanced understandings of the world. I mean that just as I made it through high school and college without a single day of economics education, so does pretty much everyone else. Literally everything I’ve learned about economics has been self-taught. And in that regard, I think “the system,” whatever that means, our education system, society writ large, whatever, has failed me, and continues to fail current and future generations of Americans. I mean that you literally cannot have a reasonably educated and sophisticated understanding of politics and society without an understanding of basic economics. This is a disservice to all of us as a general citizenry, when most of our educated, voting adults pretty much know nothing about economic fundamentals.

And it’s not just politics. It’s personal. Understanding basic economic concepts has drastically improved my thinking and decision making in exponential, innumerable ways. I literally cannot imagine my life, thinking about politics, analyzing situations, or making decisions without knowing about things like opportunity cost, marginal utility, economies of scale, or comparative advantage. I cannot imagine how I could effectively analyze or understand pretty much anything about the world without these conceptual tools. Economics is in a very real sense an exercise in pure logical thinking. It’s about as close as you can get without using Actual Math or formal logic. That’s because it requires logical formulations and connections to make sense. It requires definitions and axioms (for example supply and demand and their effect on each other). It requires clear formulations and connections that can be reduced to formal logic terms such as “If A, then B” or “If A, then not B” (ceteris paribus reasoning, for example). You have to logically connect concepts and conditions to understand how they work together. It’s not a matter of interpretation, there is a right and wrong answer, and the strength of your logic determines your ability to find the right one, or to be as accurate as possible based on the available data. This is the beauty, the elegance, and the power of economic thinking.

A couple of examples from one of my favorite authors:

1. That which is seen, and that which is unseen

A very common economic fallacy, as well as general human cognitive error, is to evaluate a choice or an action by a very obvious (usually positive) effect, but to ignore a less obvious (usually negative) effect, which may precisely offset or even be greater than the apparent effect/benefit. Here’s an example: a trade policy, tax policy, subsidy, or other government action that benefits one group of people, let’s say farmers. Giving a generous tax break or subsidy or trade protection to this one group, on its face, at first blush, seems like a great thing…look at all the farmers we’re helping. Look how much better off they are. Isn’t it wonderful? How can you be against it? Do you hate farmers…?

What most people don’t see, because they’re not used to economic thinking, is that the benefits are obvious because they’re focused on a (relatively) small, discreet, graspable group of people, but the costs are distributed to everyone else in society. We may enact a policy that will help farmers, but the cost of that policy is that the cost of their goods rises for everyone else, or that the rest of us pay for their subsidies in other ways, perhaps in higher taxes. This is a tradeoff, and perhaps it is one we want to make, but most people are not even aware that we are making it, and therefore the tradeoff is not debated or factored in when crafting this policy. And we certainly ought to discuss if we do in fact want to make any of the necessary tradeoffs for any particular policy.

Again, benefits are focused, but costs are disbursed. We have to realize this whenever we craft any sort of economic policy. Everything has to be paid for. Yes, everything. Literally, everything. And we rarely ask what the costs are for our particular pet projects, and are typically discouraged from doing so if we try to bring it up. This actually raises another point, that everything has a cost, and we can’t just do everything that we’d like or that seems like a good idea, because we can’t afford it. That’s its own issue, but related to this one. If more people thought about the tradeoffs and costs involved in any particular policy, I believe most people would be a lot more conservative in their pet projects designed to help this or that particular group.

This is a long essay discussing this topic, but you can understand the principle well enough just reading the introduction and Part I.

In the department of economy, an act, a habit, an institution, a law, gives birth not only to an effect, but to a series of effects. Of these effects, the first only is immediate; it manifests itself simultaneously with its cause — it is seen. The others unfold in succession — they are not seen: it is well for us, if they are foreseen. Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference — the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen, and also of those which it is necessary to foresee. Now this difference is enormous, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favourable, the ultimate consequences are fatal, and the converse. Hence it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good, which will be followed by a great evil to come, while the true economist pursues a great good to come — at the risk of a small present evil.

In fact, it is the same in the science of health, arts, and in that of morals. It often happens, that the sweeter the first fruit of a habit is, the more bitter are the consequences. Take, for example, debauchery, idleness, prodigality. When, therefore, a man absorbed in the effect which is seen has not yet learned to discern those which are not seen, he gives way to fatal habits, not only by inclination, but by calculation.

This explains the fatally grievous condition of mankind. Ignorance surrounds its cradle: then its actions are determined by their first consequences, the only ones which, in its first stage, it can see. It is only in the long run that it learns to take account of the others. It has to learn this lesson from two very different masters — experience and foresight. Experience teaches effectually, but brutally. It makes us acquainted with all the effects of an action, by causing us to feel them; and we cannot fail to finish by knowing that fire burns, if we have burned ourselves. For this rough teacher, I should like, if possible, to substitute a more gentle one. I mean Foresight. For this purpose I shall examine the consequences of certain economical phenomena, by placing in opposition to each other those which are seen, and those which are not seen.

2. Comparative advantage

One thing you will find in common with all professional and lay economists is a universal disapproval of trade barriers, tariffs, and protectionism. This is not because they don’t value the farmers, merchants, and tradesmen of their own country, or that they do not have proper patriotic feelings. It is because they understand basic and universal economic maxims. One such maxim is that every country, society, and culture has its own unique advantages for producing goods, and we all benefit when everyone uses them as freely and as maximally as possible. Conceptually, there is a bit of “what is seen and unseen” in this as well, but has the additional condition of specific advantages residing in each discreet group of people.

A very easy example of this is the environmental conditions for growing natural produce. It is probably possible to grow oranges, for example, in Minnesota. You could grow them for a few months in the summer, and conceivably build indoor facilities to grow them indoors year-round. But though such a thing is economically possible, it is not wise. We could do it if we tried, but it is obviously much more advantageous to everyone if oranges are grown in a climate naturally suited to their thriving, all year long, say in Florida.

As The Man Himself put it:

Labor and Nature collaborate in varying proportions, depending upon the country and the climate, in the production of a commodity. The part that Nature contributes is always free of charge; it is the part contributed by human labor that constitutes value and is paid for.

If an orange from Lisbon sells for half the price of an orange from Paris, it is because the natural heat of the sun, which is, of course, free of charge, does for the former what the latter owes to artificial heating, which necessarily has to be paid for in the market.

Thus, when an orange reaches us from Portugal, one can say that it is given to us half free of charge, or, in other words, at half price as compared with those from Paris.

Now, it is precisely on the basis of its being semigratuitous (pardon the word) that you maintain it should be barred. You ask: “How can French labor withstand the competition of foreign labor when the former has to do all the work, whereas the latter has to do only half, the sun taking care of the rest?” But if the fact that a product is half free of charge leads you to exclude it from competition, how can its being totally free of charge induce you to admit it into competition?

To take another example: When a product—coal, iron, wheat, or textiles—comes to us from abroad, and when we can acquire it for less labor than if we produced it ourselves, the difference is a gratuitous gift that is conferred upon us. The size of this gift is proportionate to the extent of this difference. It is a quarter, a half, or three-quarters of the value of the product if the foreigner asks of us only three-quarters, one-half, or one-quarter as high a price. It is as complete as it can be when the donor, like the sun in providing us with light, asks nothing from us. The question, and we pose it formally, is whether what you desire for France is the benefit of consumption free of charge or the alleged advantages of onerous production. Make your choice, but be logical; for as long as you ban, as you do, foreign coal, iron, wheat, and textiles, in proportion as their price approaches zero, how inconsistent it would be to admit the light of the sun, whose price is zero all day long!

Simply put, every society and region has its own economic advantages, whether it be advantages of nature, a particularly developed and sophisticated industry, a highly skilled workforce (generally or in specific areas), cheap labor, the list is endless. When we do not restrict trade between all of these splendidly diverse regions and people, we all benefit, by everything being cheaper and more readily available in greater quantities than would be if we institute tariffs or other trade barriers to protect our own “hard working, indigenous” whatevers. Protectionism is, economically speaking, always bad, because it raises the cost and limits the supply of everything it touches. Again, this is not advanced, mathematical economics, accessibly only to calculus geeks. This is basic, common sense knowledge that allows us to maximize everyone’s economic and material well-being, and saves us from costly errors harming not just society in general, but the very people we seek to protect with trade barriers.

As I said, I’m no economic genius. I couldn’t calculate a supply and demand curve to save my life. But I know what one looks like, and have seen plenty of them. I can’t punch up a formula to calculate producer surplus or consumer surplus, but I know what they are, conceptually, and this basic economic knowledge allows me to rationally analyze the world around me, political decisions, and economic decisions on both a personal level and a societal level. I don’t consider my economic understanding to be advanced, but it is still greater than almost everyone I encounter when I discuss economic subjects. I think my grasp of economics is the bare bones baseline required to understand our world, and I think it’s a crime that we seem not to care about it as a society, and that we completely neglect it in the education of our young people. To have a functional, rational society, everyone should have at least a basic understanding of democratic and republican principles, our constitutional history and framework, and the core economic principles that dictate the success, failure, and cost of our political policies.

If I could snap my fingers and change one thing about our society, it would be to require at least two years of basic economics in high school and one in college (non-math intensive for the math-challenged), as a pillar of being an educated citizen with an ability to fulfill your basic civic duty. Until we make basic economic literacy a pillar of our education system and civic culture, we are likely to continue the economic and political deterioration of the last few years, and eventually, the consequences are going to catch up to us, in dramatic and painful fashion.

“I was surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined, but I had the satisfaction of seeing them diminish”

Ben Franklin

I leave you with this: a great text, from The Great Man Himself. I have a few other recommendations for economics reading, more short essays with great economic realizations and truths that you can get through in one sitting, but I’ll save those for later.

Farewell, until next time.

If you liked this article, please subscribe to my blog by clicking the blue “Follow” button in the upper right corner (at the bottom of the article if you’re on your phone or tablet) to receive an email every time I post, which isn’t that often. And of course feel free to share it if you know someone else who may enjoy it.

“A polymath is someone who is interested in everything, and nothing else”

While I’m not much of a drinker, I do like a sip or a glass or two now and then. A glass of wine or scotch goes well with a night at a jazz club, a nice dinner, an evening with friends, and melancholy thoughts. Even, as I discovered this week, occasionally with writing.

My baseline scotch is Macallan 12. It’s nice and smooth, just a little dark, and not too peaty. I discovered a similar style of scotch in a brand called Monkey Shoulder, which a friend bought for my birthday a few years ago (and another friend drank 3/4 of while visiting from California). Again, smooth, a nice little punch, and not very peaty. Recently, while frequenting one of my favorite bars that in my opinion has the best burger in Minneapolis, I tried a glass of Arran 10 year (page 8 on the menu). It’s one of their more affordable scotches, but I like it better than most of the more expensive ones I’ve had.

Since I drink very little, a bottle at home will last me a long time. But, I like to have a little variety. Last weekend I bought myself a bottle of Macallan 12 to have at the ready, and this weekend I bought a bottle each of Monkey Shoulder and Arran. Now I’ll have a nice little stock ready whenever I fire up some Coltrane, find myself in the mood to watch La-La-Land, or have some friends over to listen to music and solve the world’s problems.

What’s your favorite scotch? Do you have any suggestions? I’m always willing to learn.

Here’s what my completed collection looks like:

A coworker asked me this week what I’ll be doing for St. Patrick’s Day. I told him “Staying inside, locking my doors, and boarding my windows.” While I love and respect Irish culture, what this holiday has turned into is literally my least favorite day of the year to go outside and venture out and about. It is the ultimate “Bro Holiday,” and when it comes to being around wasted bros, young and old, yeah thanks, but no thanks.

One year when I was living in New York City, I went out at night and was getting more and more pissed everywhere I went because I couldn’t figure out why there were so many douchebag bros everywhere I went. It actually took me a couple hours and a few bars to realize it was St. Patrick’s Day. About ten seconds after my “Ahhhhhh, FUCK!” moment, I bounced the hell out, ran to the subway, and zipped home as fast as I could.

That being said, while in my opinion there is not much to love about the holiday, there is MUCH to love about Irish people and Irish culture. The first time I ever met an Actually Irish Person was at a pub in a small town in Germany when I was 19. It was your standard fare Irish pub, small, wooden furnishings, a husband and wife acoustic duo playing on stage. I ended up chatting with a bearded Irish man in his 50s and his gorgeous blonde wife who was probably around 35.

Two things stand out to me from that conversation. One was when he put his arm around me and said “Son, if yeh ever want to learn how to drink and fight, come to Ireland and I’ll show yeh.” He was a pretty warm, friendly guy, and I’m pretty sure this was a serious offer. The second is a very strange and funny scenario that happened upon our parting. As I was leaving, his lusty, busty, gorgeous wife gave me a long, warm, dare I say sensual good night hug, which positively tingled my young virginal body with delight from head to toe. And I’m sure she knew it. After holding and squeezing my quivering, frail body for a few seconds, she smiled and let me go. When I then went over to her husband and shook his hand, he gave me a hearty handshake, smiled his big friendly smile, said something about how good it was to meet me, and then, still holding our handshake, lightly punched me in the jaw and said “And stop looking at me wife like that!!!” before laughing like a bear and pulling me in for a hug.

If that’s not Irish, I don’t know what is…

Many years later, when I was in my early 30s, I dated an Irish cop for awhile. Gráinne was the very definition of a bad ass bitch. How was she bad ass? Oh, let me count the ways. First, I should relate the story of how we met. I was drinking at my favorite neighborhood bar in New York, sitting alone and relaxing. I saw her and was just dumbstruck by her beauty. She was your classic Irish beauty, tall, slender, dark haired and fairest skinned. She also had a presence, an aura, a magnetism. She was with some friends, and it would have been the height of uncouthness to approach her this way. So, being sly, when I noticed one of her friends walking back into the bar after having a smoke outside, I gently touched her arm to get her attention, and said “I think your friend is gorgeous, can I ask if she’s single?” She told me that she was, indeed, recently single, divorced in fact. BUT, the group of people she was hanging out with were her husband’s friends, so unless I enjoyed receiving a good beatdown behind the bar, I should very much stay away from her tonight. So I just said “Well, tell her I think she’s amazing, and if she’d like to talk to me, let me know.” Not long after, her friend returned with a slip of paper and said “She likes you, she said to call her.” My heart went utterly aflutter.

So besides being gorgeous and having a magical aura, why was Gráinne so bad ass? Well first of all, she was married to a man for a long time, working and paying the bills while he went to medical school. I learned that she was divorcing him just as he was about to graduate. To me that speaks very highly of her honor, integrity, and self-respect. I don’t know if there are many women, or men for that matter, who would support a spouse through something as challenging as medical school, and when they feel it’s not working out for them, leave just before the payout, so to speak. This is really a high-caliber person sort of thing to do. I think that most people, even if they thought divorce was inevitable, would have lied to themselves and their loved ones for at least a few years in the expectation of more favorable terms should the divorce come to pass. I really can’t say enough about how much I respected her for this move. To this day this is one of the most honorable things I’ve seen a person do.

The other thing that made her so bad ass was her unicorn-like combination of beauty and toughness. She was all of 5’10”, yoga-slender, ephemeral…and also a New York City cop, working midnights in some of the toughest neighborhoods in the city. I must now relate another story that conveys both her beauty and her integrity. She was approached by a modeling agent at one point in her 20s, and picked up to model for Versace for a bit. She made about $25,000 that month. But she only lasted a month. She said the models were as shallow and vapid as you’d expect them to be, and being a smart chick, could not stand being around, in her words, “those dumb bitches” all day. So she quit. Again I ask, would you quit a high status, lucrative modeling job because you were annoyed by the people you were working with? Let me answer for you: NO. I sure as hell wouldn’t. I might tough it out for a few years and sock some cash away, but I’m pretty sure that’s a move I would not make.

On the other side of the coin of her beauty was her toughness. She would often text or call me at 3 or 4 in the morning telling me about how she just chased down and tackled some drug dealer in Washington Heights, or had to fight a guy who was resisting arrest. She absolutely loved that aspect of her job, and was thrilled every time it happened. She also used to send me texts from the gun range about how firing her pistol turned her on, how shooting a gun was so erotic, and could she please come over in an hour. I got an unusual number of texts from her about her guns, sometimes mentioning what a pain it was driving between states with her pistol underneath her seat, talking about her favorite gun and asking what was mine, or some other quirk about gun use and ownership. She was an ephemeral fairy who liked to fight drug dealers and was in love with her guns.

How this all relates to St. Patrick’s Day is one of the best comments she ever made when I took her to my favorite Irish pub, on 72nd street. It was an off night, say a Tuesday perhaps. We were chilling in a corner eating and drinking at a table, and in walked a gaggle of bros wearing green and being all “We’re so wild, and so IIIIIIRISH!!!!” She looked at them the way you’d look at a maggot in your cheese and said “I fookin’ HATE plastic patties….” I had never heard this term before. After I stopped crying from laughter, I had to ask her what a plastic patty is. A plastic patty is someone who’s not FROM Ireland, but is more Irish than any person who actually IS. This is fucking brilliant, and perfectly describes what it is that I personally hate about St. Patrick’s Day, and many Irish pubs in general. For me, to be on a date with the most quintessentially Irish woman I could imagine, and hear this coming out of her mouth, followed by a litany of profanities, was the most wonderful thing that could happen to me.

I’ve since met other fine folks from Ireland while out and about, but these experiences are the ones that made me really develop a love and fondness for Irish people and Irish culture. While I find the whole get-up about the holiday pretty shallow and fabricated, I do love that the Irish people have a rich culture, a sense of honor and tradition, and most of all, a sense of humor. If I ever find myself invited to celebrate with true Irish people on this day, then you can absolutely count me in. Until then, you can summarize my feelings on St. Patrick’s Day as this:

Happy St. Patrick’s Day everyone, have fun out there!

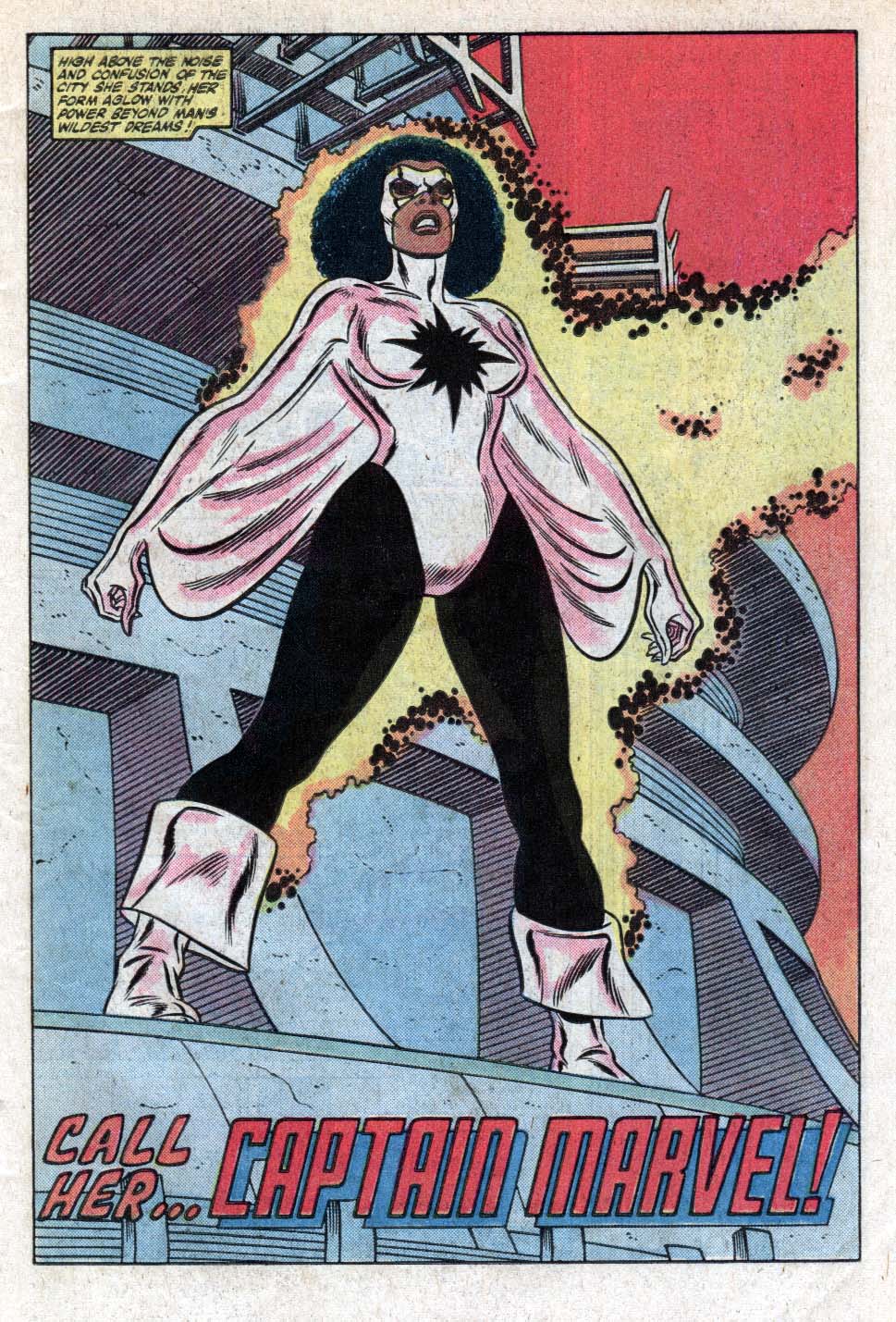

As a lifelong Marvel comics fan, who has been reading them since Captain Marvel was a black woman (in 1982) and led the Avengers (in 1987), I have a stronger than average interest in Marvel movies, understanding of their characters and story lines, and emotional investment in their success.

I’m about to rush out for dinner, then see a movie about a character I’ve been following for over 30 years. Marvel’s movies in the Avengers series haven’t let me down yet, but the previews for this one leave me with one underlying concern: is Captain Marvel a Mary Sue? Because she’s definitely being marketed as one.

What is a Mary Sue? If you’re even a moderate movie lover, this is a term you should be familiar with. If you’ve seen the latest Star Wars movies, you definitely know what a Mary Sue is, even if you weren’t aware of that term or had heard the concept articulated before.

I don’t have the time to explain it right now, and honestly it’s more fun to discover what it means while being entertained. I only found out about this last year, in a discussion about Star Wars with some friends. Someone said “Rey is a Mary Sue” and I said “Who is a whatsa whosis…?” And then they showed me these:

So I’ll be crossing my slick, buttery fingers tonight that Marvel has not fallen into this trap, and does a better job of character development than Star Wars/J.J. Abrams did.

Excelsior!

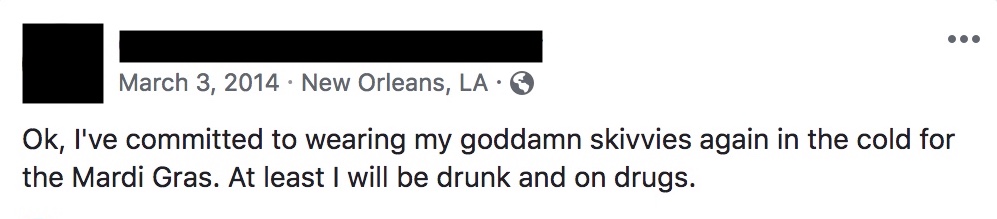

As some of you may know, I moved to New Orleans in 2009, to the burning Heart of Darkness, the French Quarter itself. That’s right, that is indeed the year the Saints won the Super Bowl, and I saw almost every game at different bars in New Orleans, and watched them beat the Vikings in the NFC championship at a swanky society party in the Roosevelt Hotel. I spent three glorious, heart-wrenching years in New Orleans, two in the Quarter, and one in the suburbs. There is an essay, or a book to be written about that someday, certain to be assisted by copious amounts of wine and absinthe.

But for now, in honor of Fat Tuesday, I present:

You’re welcome.

“Sometimes you have to fight, even if you know you’re going to lose.”

— A Wise Man

I had this thought yesterday, as I was driving to the gym, over-intellectualizing something, as usual. There was no real particular context, I was just pondering life in general…my life, historical figures, etc. There are some prominent examples from American history that immediately come to mind, like George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, and the men who fought with them. When they took up their fights, they seemed impossible, and the prevailing wisdom and inescapable logic of their day was that they were going to lose, quickly and badly. But they fought nonetheless because they believed it was the right thing to do, knowing that they would likely lose everything, including their lives.

Now there is another lesson from those two examples, which is important, but not the one I have in mind: sometimes a fight may seem impossible, but you fight anyways, and even against impossible odds, you may win. So many wars and battles teach this lesson, as well as many less dire and existential social, political, and interpersonal struggles. This is definitely an important thing to know.

But so is the original point: sometimes, even if you sincerely know you’re going to lose, you have no way to win, you expect to be beaten, and your fight turns out exactly as you expect…you have to fight anyways. Because to be a person, to be a man, to be a woman, you have to have something you believe in, someone whose back you have, something worth fighting for or dying for, or you’re just a mindless beast. There has to be something you stand for, something you believe in, someone you would protect, even at the greatest cost to yourself, because otherwise you’re simply a brute living on selfish instinct.

I heard a line in an overlooked movie 20 years ago that said this well, that was actually my first inspiration for this insight. I couldn’t remember the exact line, but I remembered the sentiment, and it has stayed with me, and bored its way ever deeper into my psyche, ever since. I reflect on it whenever I think deeply about what I would do for who and what is important to me. After 20 years, I have finally found it, researching for this piece. I hope it makes you think half as much as it has me, and helps you clarify what you care about and what you would fight for as it has done so well for me.

“I condemn those indifferent mortals, who either never form opinions, or never make them known.”

— Alexander Hamilton